Medieval wealth of life

“A growing human population is not a killer of biodiversity; what matters is what people do to the environment," says Prof. Adam Izdebski, PhD habil., from the Interdisciplinary Centre for Modern Technologies at the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń.

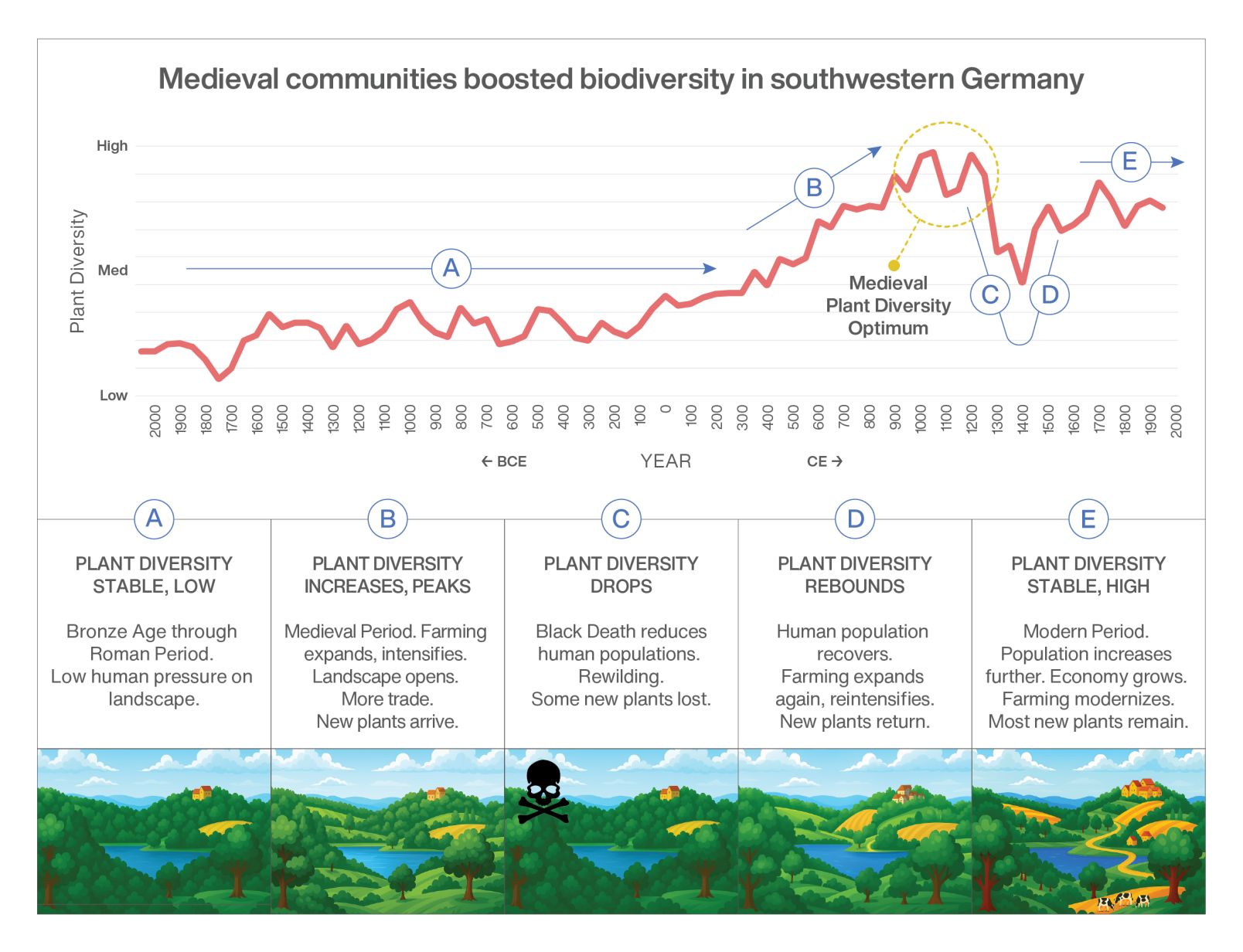

Biodiversity is the entire richness of life on Earth—from microorganisms, through plants and animals, to complex ecosystems. It is not only the number of species but also the genetic diversity within them and the complex relationships between them. All these elements are interconnected and influence the functioning of our planet because they provide ecosystem services: pollination, climate regulation, water and air purification, and soil fertility. The loss of biodiversity is caused, among other things, by the unsustainable activities of humans, who consume natural resources faster than nature is able to replenish them. Paradoxically, human activity also contributed to a huge increase in biodiversity in the period from around AD 500 to around AD 1000. A team of researchers writes about how medieval communities increased biodiversity around Lake Constance in the article Cultural innovation can increase and maintain biodiversity: A case study from medieval Europe, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The principal author of the article is Prof. Adam Izdebski.

The data indicate that the increase in biodiversity was driven by cultural innovations in agriculture, land management, and trade during the period when the foundations of medieval Europe were taking shape," says the researcher from ICNT. “It is only now that we are beginning to lose the biodiversity that was achieved in the Carolingian era and in the early Middle Ages."

The Archive of Nature

Prof. Izdebski's team examined regions of Europe and noticed that the history of biodiversity is best studied in Baden-Württemberg, that is, in the area of Lake Constance and the Black Forest. Such analyses are carried out on the basis of pollen data collected by Prof. Manfred Rösch of the University of Heidelberg, and the researchers additionally combined them with historical and economic data gathered, among others, in the archive of the Abbey of St. Gall—the oldest monastic archive in Europe.

credit HGS for MPI GEA, 2025. Images in the figure generated with ChatGPT (© OpenAI)

Plants produce pollen in the process of reproduction. It is transported by wind and waterways, and besides pollinating plants, it settles on the bottoms of lakes and peat bogs. Over hundreds of years, it accumulates as a tiny fraction of sediments and creates a kind of archive of nature from which scientists can extract a sediment core, conduct the appropriate analyses, and count the pollen. From a boat or raft, a probe is lowered, which drives a plastic tube into the bottom; the tube is then pulled out, cut open in the laboratory, and samples are taken—for example, every centimetre or every half-centimetre.

Pollen has very diverse shapes, which allows us to assign it to specific groups of plants, or even species," explains Prof. Izdebski. “This research is probably the life's work of Prof. Rösch. It has the highest temporal resolution in Europe, meaning it shows changes almost decade by decade, and at the same time its author carried out perhaps the most precise taxonomic analysis possible—very accurately identifying species or families depending on how distinctive the pollen morphology is."

The palynologist counted several hundred pollen grains in each of the dozens and hundreds of sediment samples taken from various cores across the region. On this basis, the researchers in Prof. Izdebski's team calculated biodiversity indices—the same ones that are calculated in modern ecosystems by determining the species occurring per square metre of surface area. Thanks to this, the researchers had detailed baseline data.

“Adam Spitzig, a doctoral student from the American universities of Stanford and Harvard who works with us, analysed data covering almost 4,000 years and noticed that between around AD 500 and around AD 1000 the Lake Constance region experienced a true surge, a revolution, a leap in biodiversity," says Prof. Izdebski. “This was very interesting, and the period was certainly not accidental. We assembled around the palaeological results a group of historians working to understand what was happening there economically, politically, and socially during that time. By combining this knowledge, we were able to explain which social process underlies the biodiversity revolution we discovered."

A New Economy

Prof. Izdebski admits that he is a historian who became an ecologist. That is why he has begun to analyse in depth certain topics about which he previously had only popular-science knowledge, and he expected that human activity by definition has a negative impact on biodiversity. In the past, however, the opposite was true—generally, in science it is accepted that over the last few thousand years, the increase in biodiversity in Europe was closely linked to an increase in population density in a given area. “When Adam Spitzig and I began analysing various data, it turned out that it is not population size but what people do that has the greatest impact on biodiversity," admits the researcher from ICNT. “Lake Constance lies at the foot of the Alps, on the border of today's Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. In antiquity, this was a region of the Roman Empire; there were quite a lot of inhabitants, the population density was fairly high, and biodiversity much lower. Of course, population size is not entirely irrelevant, because people must be clothed and fed, and to do certain things you need a sufficient number of hands to work."

photo Adam Spitzig

But in the 7th, 8th, and 9th centuries an entirely new form of economic management begins. In documents we can see that in the 8th century a monastery is founded, and its “managers" order peasants to introduce the three-field system, instructing them on how to do it. The emergence of the three-field system creates a mosaic of landscapes. There are fields cultivated in winter, in spring, and those lying fallow; catch crops begin to be introduced; horses appear as draught animals. What is crucial is the emergence of large landholdings, which create a whole package of agricultural and managerial innovations that, in effect, produce a highly biodiverse landscape.

In addition, the region slowly begins to play an increasingly important economic role in the part of Europe that became very impoverished after the fall of the Roman Empire. The Abbey of St. Gall, apart from having land estates, also has trade contacts on the other, southern side of the Alps. Thanks to these, it starts experimenting and introducing new crops. With the seeds of cultivated plants come the seeds of weeds—that is, synanthropic plants. A highly varied landscape mosaic begins to emerge, with many transitional ecosystems between those created by humans and those that are natural, and this generates an entirely new quality in terms of biodiversity.

Reference Points

“The Carolingian ecological revolution—that is, a particular mode of economic management—emerges in the second half of the first millennium and spreads throughout Europe. The biodiversity we now strive to protect was created by humans. We must answer the question of what we actually want to achieve, what we want to return to," notes the historian and ecologist from ICNT. “What is our point of reference? In English, we call this phenomenon shifting baselines—that is, a shifting foundation, a changing point of reference."

photo Sara Saeidi (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Project number 443614159)

When we look at Europe in the early Holocene, and especially the mid-Holocene—about 5 to 7 thousand years ago—we see forests everywhere, and the same would be true today if humans completely ceased to interfere with the natural landscape. This is what happened after the fall of the Roman Empire in Central Europe, between the Elbe and the Vistula and Bug rivers, where there were almost no people, and the forest had several hundred years to regrow, causing biodiversity to decrease, because a forest is a biodiversity-closed structure. It is extensive, like today's monocultures, and allows for the existence of only a specific set of plant, animal, and insect species. A forest must be opened for other, new species to appear.

During the last glaciation and the early Holocene, large herbivores lived on Earth—for example elephants, rhinoceroses, bison, or giant deer—which served as “openers" of the landscape and prevented vast areas from becoming overgrown with tall forest. Thanks to them, the landscape of the previous interglacial was probably more mosaic-like than in the mid-Holocene, before humans in the Neolithic and later began to interfere heavily in ecosystems. In the Carolingian era, in addition to the change in land management, the space was made accessible to animals such as cows and horses, although of course no one at the time was thinking about the fact that they were partially recreating conditions from before the extinction of the great herbivores.

This situation draws our attention to the fact that, for example in the mountains, we need traditional grazing and traditional agriculture because they maintain biodiversity," says Prof. Izdebski. “If we leave the local meadows without intervention, in 100 years they will no longer be so diverse, because nature will tend toward a certain optimal plant and animal community—toward some stable, final state. The human being is, in a sense, the curator of the ecosystem."

Biodiversity in the region studied by the researchers remained at a low level until around AD 500, when it began to rise sharply. Later, fluctuations appeared, but already at an entirely different, much higher level.

The first significant decline in biodiversity is noticeable in the 14th century, during and after the Black Death—the plague pandemic during which, in some regions, between 30 and 50 percent of the population died. Two or three waves of the epidemic destroyed the social structure; around Lake Constance, too few people survived to maintain the existing landscape.

New Times

In the 16th century, everything seems to return to the right track. The decline in biodiversity lasted from three to five decades; afterwards, there is a plateau and a rebound. This entire downward-and-upward episode took about 150 years. Biodiversity increased, but it never again reached the level from before the epidemic—despite the return of species diversity, the earlier balance of diverse ecosystems did not reappear.

We must distinguish between diversity in the sense of number and in the sense of balance," explains Prof. Izdebski. “In a given area we may have plenty of species, but three that dominate. That dominance of certain plants begins after the Black Death."

But this change is not caused only by the death of many people and the lack of labour. In the 16th century, capitalism began to take shape, along with industrial production; people wanted to earn more and more while not adding tasks to themselves. Cities expanded, and in them the number of workers grew—workers who needed to be clothed and fed. The social structure and the organisation of management changed. Regional specialisation and pan-European economic integration began to take shape to a much greater degree. The region under study opted for development in the direction of linen textile production, gradually moving toward monoculture crops. Merchants selling textiles from the Atlantic to Kyiv needed raw material for fabric production. In the 16th century, this process expanded across all of Europe. One need only look at Poland, which during this period began to specialise in grain production. The changes accelerated even further in the industrial era.

fot. St. Gallen, Stiftsarchiv, IV 345 (Private charter). https://www.e-chartae.ch/en/charters/view/531

“The same plants continued to exist in the landscape, but it was no longer so balanced," notes Prof. Izdebski. “That is why one can say that both ecological farming and farming based on large, modern, holistic-thinking estates are, on the one hand, capable of fully and healthily feeding people, and on the other—are a path to preserving biodiversity."

The decline in biodiversity began in the 19th century and accelerated in the mid-20th century. This was connected with a transition to what is, in essence, an anti-rational optimisation of agriculture—industrialised, mechanised farming that sought to create large-scale uniform surfaces. In addition, this period encompassed two world wars. “We can see the impact of the First World War on the landscape even in Greater Poland, that is, in an area where no military operations took place, similarly to the region we studied," says Prof. Izdebski. “In Greater Poland, it was probably caused by large-scale conscription."

The Optimum of Biodiversity

The main message of the article is a rejection of the thesis that a growing population is the killer of biodiversity; what matters is the action people take in the natural environment. The period of peak pre-industrial population was simultaneously the peak of biodiversity. The authors of the article have called this time the medieval biodiversity optimum. “From the perspective of popular knowledge, we show that humans are not a catastrophe for biodiversity," summarizes Prof. Izdebski. “From the perspective of scientific knowledge, we demonstrate that in the Holocene—that is, over the last 10–12 thousand years—it was not the case that the more people, the more biodiversity. It does not increase linearly. Population size affects biodiversity, because it is a matter of labour-force potential, but what matters much more is what the economy looks like and how ecosystems are managed."

NCU News

NCU News

Social sciences

Social sciences

Natural sciences

Natural sciences

Humanities and arts

Humanities and arts