Humanities and arts

Humanities and arts

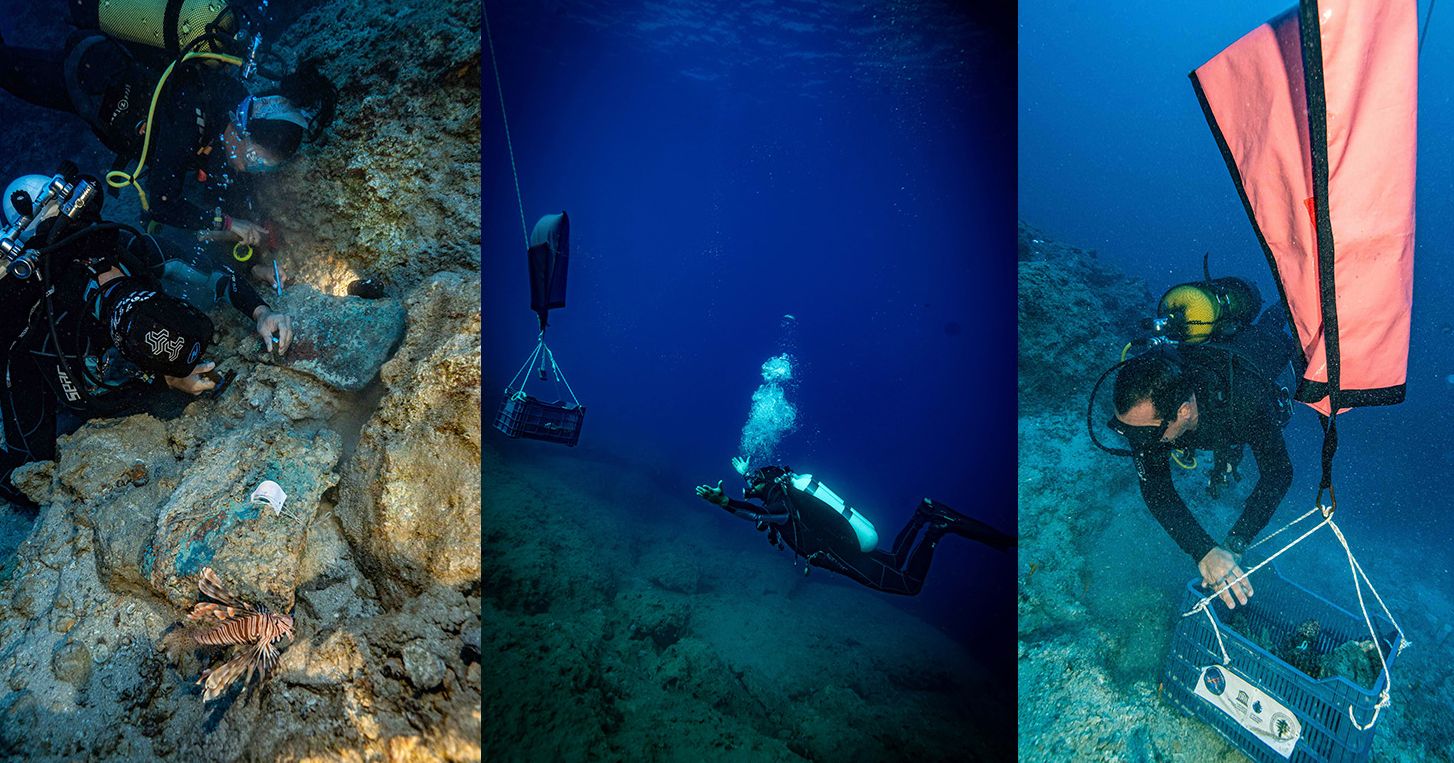

Prehistory sunken in the sea

Scientists from the Centre for Underwater Archaeology, Nicolaus Copernicus University, have examined a sunken shipwreck from the Bronze Age. It is probably the oldest vessel in the world which transported copper bars.

According to a definition, a wreck is a sunken or damaged ship. People most commonly associate it with a rusty iron construction or a wooden ship framework lying underwater. The attitude presented by archeologists dealing with underwater exploration is different, however. The cargo from a ship dating back to the Bronze Age found near the Turkish coast is what they call the shipwreck as well, although no construction remains have been found so far. “Frankly speaking, up till now, we have found no single wooden piece that could be considered a part of the ship framework and the same refers to anchors. I think the anchors must have been cast when the ship was being pushed onto the rocks, reveals dr hab. Andrzej Pydyn, Prof. NCU from the Centre for Underwater Archaeology, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń. On Uluburun (the shipwreck discovered in the 80s of the 20th century, ed.), ten of them were found, which means the ship crew made an attempt save the vessel by casting anchors, but they unfortunately failed. All the same, we are convinced that copper bars have not been found lying on the seabed for a reason any other than the catastrophe and this fact justifies why what we have examined is called the wreck.

It certainly is the wreck

Firstly, the location proves it. Leaving the Gulf of Antalya and going to the open sea is a navigationally dangerous operation: the current and the wind directions change. On Cape Gelidonya, there is a lighthouse near the place where another Bronze Age shipwreck was found in 1958. The whole area is considered paradise for underwater archeologists due to the fact that numerous ships from different chronological eras sank there. Moreover, it is difficult to imagine what else scientists could discover here since accessing this location from the coast is virtually impossible. The basin is surrounded by steep rocks growing directly out of water. Additionally, the route leading to the Gulf of Antalya was very important throughout most of the Bronze Age. It constituted a natural waterway which sailors followed when they headed west, towards the Aegean Sea, or east, towards Cyprus and Syria Palaestina.

photo Mateusz Popek

Secondly, when diving and carefully observing water, one can discern copper bars covered with layers of concretion and forming a steeply falling slope. The historical treasure is located at the depth of 35 meters to 50 meters under water. A part of the cargo can be found even deeper.

Thirdly, the manner in which the cargo is arranged also suggests a sea catastrophe. The ship must have been pushed onto the rocks and sank rather quickly. The vessel was heavy and once the hull was damaged, it immersed rapidly, and the cargo slipped down the slope which is very steep there.

Sometimes, there were single bars; in other places, due to the structure of the sea bed, the bars were piled, informs the archeologist from Toruń. If we systematically explore the place, other artefacts which will extend our knowledge of the shipwreck will emerge.

Fourthly, lack of wood is nothing exceptional. Within the Mediterranean Basin, each wooden piece of a ship which is not covered with some bottom sediment or cargo is eaten up by the naval shipworm (Teredo navalis). The species can be compared to the big bark beetle which consumes wood very quickly. It occupies water which is sufficiently salty and warm. The Baltic Sea is not a suitable habitat for the naval shipworm, and thus, the shipwrecks found in this region are far better conserved. Due to the climate change, however, the presence of the bug has been observed in the western regions of the Baltic Sea. It already exists by the Danish and German coastline . According to the scientist from the NCU, there is an approximately 20 percent chance of finding wood.

photo Mateusz Popek

For researchers, the main objective was to prepare documentation, primarily photogrammetric (i.e. involving the reconstruction of shapes, sizes, positions of objects relative to each other in the area based on photograms), 3D models of the seabed and historical objects placed there, and collecting the noticed objects. On the site, characteristic copper bars in the shape of cattle hide were the most important treasure. Each bar weighs around 20 kg, and about 30 pieces have been brought in so far. However, there are many more of them still underwater.

Underwater discoveries

Scientists feel excitement when even single objects made of bronze are found in northern Europe. In the meantime, in the Mediterranean Sea, the underwater archeologists have discovered a shipwreck loaded with copper used for the production of bronze. It is not the first and the biggest vessel of that kind discovered by the Turkish coastline, but it is possibly the oldest one. The discovery can prove the claim that copper bars in the shape of cattle hide appeared earlier than 1500 BC, i.e. earlier than it assumed by scientists.

Shipwrecks from the Bronze Age are exceptional mainly due to their place in chronology. So far, archeologists have discovered single smaller vessels in different parts of Europe or the Mediterranean Basin, but only three of them were loaded with copper.

photo Andrzej Romański

The first one (named Gelidonya after the place it is located in), dated back to 1200 BC, was found by Kemal Aras, a sponge diver, in 1954. Four years later, Peter Throckmorton, an American journalist and amateur archeologist who also searched for antique shipwrecks, learnt about the discovery. He organized first diving sessions around Cape Gelidonya, and passed the discovered artefacts to Prof. Rodney Young from the University of Pennsylvania. Prof. Young, in turn, organized an archeological expedition to the mouth of the Gulf of Antalya in 1960 which was led by George Fletcher Bass.

“It was the beginning of the underwater archeology, and Bass became 'father of the underwater archeology', informs Prof. Pydyn. Around the same time, in the 1960s, in Sweden, Vasa was lifted from the seabed and its restoration works were initiated, and the Danes discovered sunken Viking shipwrecks in Skuldelev. By the invitation from Mr. Bass to participate in the project in 2010, I had the pleasure of working on Gelidonya. It was 50 years after the first exploration works had been organized in the site, the 50th anniversary."

On Gelidonya, more than 30 complete and several dozen fragmented copper bars were discovered. However, the most spectacular cargo was found on Uluburun (also named after the place it had been found in), the shipwreck around 100 years older than Gelidonya. Prof. Cemal Pulak from Texas A&M University who supervised the research of the shipwreck in the years 1986 - 1994 often emphasized that the ship must have been a royal vessel. The richness of the cargo has been constantly astonishing archeologists.

Many times I have been asked by journalists what kind of an archeological site I would like to discover, says Prof. Pydyn, and my answer has always been the same: another Uluburun. About 10 tons of copper and 1 ton of tin in several dozen bars were retrieved from the shipwreck. Considering the cargo, since the ratio of copper and tin required for the production of bronze is 10:1, the amounts of the metals discovered may suggest their application. It seems a certain kind of wax employed in the metallurgical processes was shipped as well. Additionally, glass, bones, wood, seeds, fruits, and other handcrafted objects were probably transported.

Oldest vessels

Throughout the past centuries, the shape of the copper bars must have changed. “Based on this, we can roughly estimate the age of the vessel., explains Prof. Pydyn. The discovered shipwreck appears to be the oldest one. Typologically speaking, the bars we are disclosing belong to the earliest remains, i.e. they are from the 16th, but also possibly from the 17th century BC. So, we are moving from the late Bronze Age to the middle Bronze Age. Gelidonya and Uluburun are associated with the Mycenaean civilization. According to earlier archeological literature, in the late Bronze Age, the Mycenaeans were those who controlled shipping and trade in the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. Our shipwreck, however, must have sailed as a ship in the times when the Minoan culture was predominant.

photo Mateusz Popek

The age of Gelidonya dates back to 1200 BC. The age of Uluburun was determined more accurately because ebony once shipped by this vessel remained at the bottom of the wreck. Owing to dendrochronological examinations carried out by Prof. Peter Kuniholm, the age of the latter ship dates back to 1305 BC. Since the subcortical layers are missing, it is assumed that the ship was constructed around 1316 BC. Nevertheless, in the scope of recent research, the exact date of the construction still remains an open question. Scientists find it difficult to establish who owned the ships. The majority of the cargo shipped by Uluburun was imported from the regions to the east from Cyprus. On the archeological site, divers also found numerous artefacts related to the Mycenaean culture. Similar artefacts were identified in the remains of Gelidonya.

It is assumed that the both ships sailed in the eastern regions of the Mediterranean Sea, explains the archeologist from Toruń. Copper, which is almost certainly connected with Cyprus, was their main type of cargo. According to research, it can be clearly seen that in the late Bronze Age the majority of copper used in the eastern parts of the Mediterranean Sea was exploited from the Cypriot deposits. The topic of tin is much more complex since its source is far more difficult to recognize. There were huge deposits of it in Sardinia or Cornwall, for example, but tin discovered on Gelidonya and Uluburun was almost surely not exploited from those sources. It seems more likely that the metal was transported from the deposits situated in the Taurus Mountains in Turkey, or from Uzbekistan in Central Asia.

The researchers emphasize that there must be more shipwrecks from the late Bronze Age because copper trade was flourishing then. In that period of time, copper ores were exploited in only a few mines of the Mediterranean Sea region, and the demand for copper was huge, explains the archeologist from Toruń. In Central Europe, the metallurgic production was related with contacts with the Anatolian, Balkan, Caucasian, and Carpathian circles; for the eastern parts of the Mediterranean Sea, Cyprus was the basic supplier of the ores. The developing Mycenaean, Minoan, and Egyptian civilizations were in need of copper.

The discovered shipwreck is waiting for the forthcoming archeological seasons. If the scientists do not find spectacular treasures, picking the copper bars from the seabed will take two or three years. "The age of the discovery is most impressive, sums up Prof. Pydyn. If not the oldest, it is one of the oldest shipwrecks. It confirms the early and complex scale of copper trade, and I think further analyses may additionally increase the value of the discovery."

Dr hab. Andrzej Pydyn, Prof. NCU, Dr Mateusz Popek, and Szymon Mosakowski, a student, all representing the Centre for Underwater Archaeology, Nicolaus Copernicus University, participated in the examination of the oldest shipwreck in the world. The works of the international team were coordinated by Prof. Hakan Oniz from Akdeniz University. The underwater archeologists from Toruń have been cooperating with Prof. Oniz for years. The scientist from Turkey has also visited Poland several times. The cooperation was intensified due to participation of the scientists in UNESCO/UNITWIN for Underwater Archaeology which is an international program for the cooperation of academic institutions dealing with underwater archeology. The objective of the program initiated in 2012 was to strengthen cooperation and exchange experience in the field of academic education, scientific research and training among higher education institutions.

NCU News

NCU News

Humanities and arts

Humanities and arts

Humanities and arts

Humanities and arts