Humanities and arts

Humanities and arts

The Second Life of the First Book

A copy of the Bible prepared, printed, and published in the mid-15th century by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz – the only one in Poland – was studied, conserved, and digitized by a team of researchers from the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń. The two-volume work is the property of the Diocesan Museum in Pelplin.

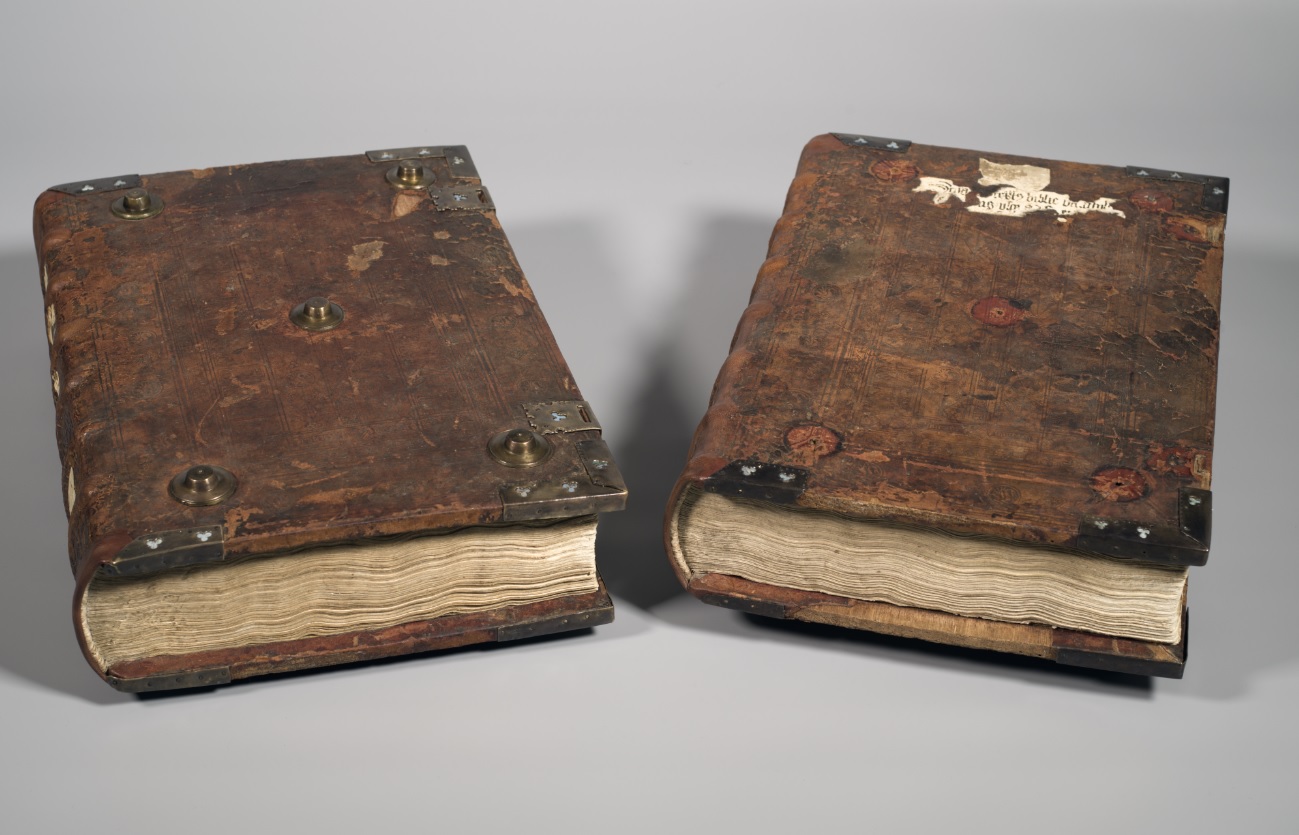

The Gutenberg Bible, also known as the Forty-Two-Line Bible, is a two-volume work produced using a printing press and movable metal type. On nearly thirteen hundred pages, it contains the text of the Holy Scriptures in the Latin translation by St. Jerome. Researchers were unable to determine exactly which year the Pelplin copy comes from. It is known for certain that it is an editio princeps (first edition, first printing) from the years 1452–1455. The print run of this historic work (considered the first printed book in history) probably numbered one hundred and eighty copies, of which only forty-eight have survived to this day. Most of these surviving copies were printed on paper, and a dozen or so – on parchment. Only 17 existing copies have survived as two-volume sets.

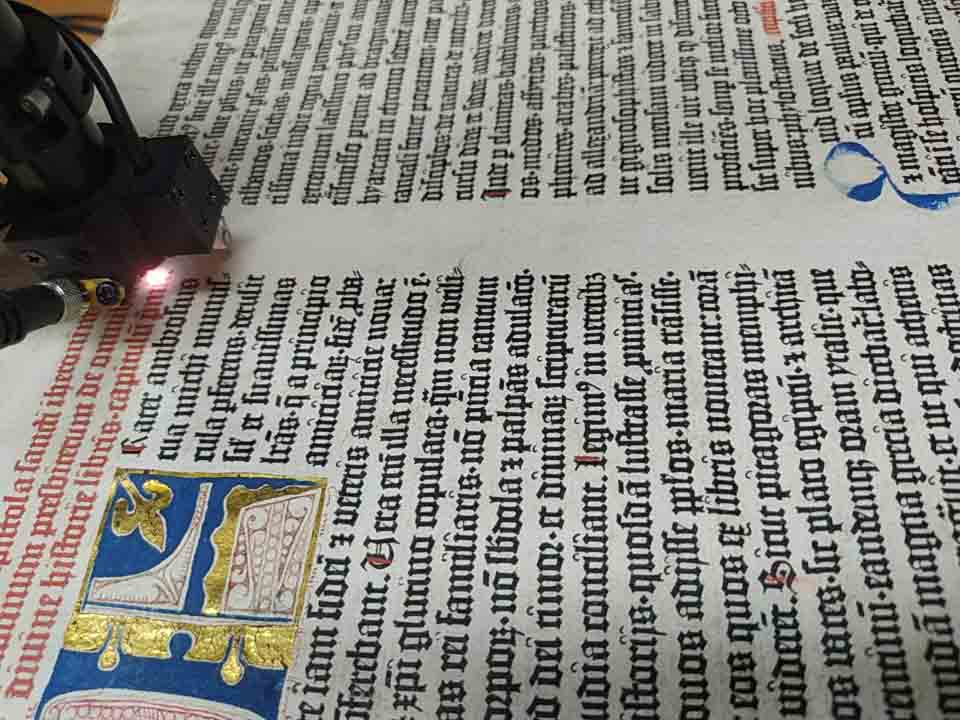

– The fact that the Pelplin Bible is a so-called prototype copy was confirmed by the exceptionally extensive multispectral imaging we applied in our research of this monument – says Dr. hab. Juliusz Raczkowski, professor at Nicolaus Copernicus University, from the Faculty of Fine Arts, coordinator of the project "We Are Saving the Pelplin Gutenberg Bible". – It is clear that there are places where the ink did not transfer, meaning the printers did not yet have experience. These places are, of course, beautifully masked. Gutenberg must have made use of the skills of an experienced calligrapher with a well-trained hand, who supplemented the gaps with ink. There are places where traces of quickly blotting the ink with a pad are visible. There is also a fingerprint – the question is, whether it belonged to Gutenberg, Johann Fust (Gutenberg's partner), or Peter Schöffer (a printer and Gutenberg's apprentice). All of this indicates that this is one of the first paper copies to come off the printing press.

photo Project archive "We Are Saving the Pelplin Gutenberg Bible"

The fingerprint is not the only defect of the Pelplin Bible. On the lower margin of folio 46r, there is an imprint of a piece of type that fell out of the press. This small mishap during work, after centuries, is a unique testimony to the printing process – a document of the shape and dimensions of the first movable type in history, none of which has survived to our times. This, among other things, significantly increases the material value of the volume.

An Extraordinary History

The edition of the Bible located in Poland most likely comes from the so-called endowment fund of Bishop of Chełmno Mikołaj Chrapicki for the Bernardines of Lubawa, who were brought from Saalfeld in Saxony in 1502. – The bishop donated part of his collection of incunabula and manuscripts from his private library to the new monastery – explains Prof. Raczkowski. – And he had a very large library, as he belonged to the intellectual elite of the time (during that period there were two such dignitaries, both from Toruń: Chrapicki in the bishopric of Chełmno and Łukasz Watzenrode in Warmia). This is confirmed by another incunabulum from the Pelplin collection, with an original note from Bishop Chrapicki on the first page, stating that he was donating the codex to the monastery of the Reformed Franciscans. We believe that the Bible also reached the monastic library in this way, because in the first volume there is an inscription "pro loco lubaviensi", identified by paleographers as early modern, that is, from the second half of the 16th century, confirming that this book was in Lubawa at that time.

After the secularization of the Teutonic state, Lutheranism became the dominant denomination in secular Prussia. The number of Catholics declined, and the Lubawa monastery deteriorated year by year. In 1564, the last monk died, the church furnishings were transferred to the bishop's castle in Lubawa, and the convent was closed. It stood empty until 1580, when Bishop of Chełmno Piotr Kostka brought new monks to the monastery, this time from the Polish province. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, the Prussian authorities carried out a suppression of religious orders. Between 1773 and 1900, all male monasteries (120) and almost 75 percent of female ones (66) were dissolved. The Reformed Franciscans in Lubawa met the same fate. Fortunately, in 1821, Pope Pius VII established new diocesan boundaries in the Prussian state. The Diocese of Chełmno was significantly expanded, and in 1824 the bishop's seat was moved to Pelplin. There, the new Bishop of Chełmno, Ignacy Stanisław Matthy, settled, who showed particular concern for the Chełmno seminary, relocated to Pelplin in 1829. He began efforts to acquire the book collections of the dissolved monasteries. In this way, the Gutenberg Bible came into the possession of the Chełmno diocesan seminary library in 1833. – The Bible was catalogued, and on the first page of the second volume, the oldest diocesan signature, C19, has been preserved – says Prof. Raczkowski. – But the journey of the volume did not end there.

photo Piotr Kurek, Tomasz Dorawa

Just before the outbreak of the Second World War, at the end of August 1939, Rev. Dr. Antoni Liedtke took both volumes of the Bible to Warsaw and deposited them in the safe of the Bank of National Economy. From Warsaw, they were transferred to the Polish Library in Paris, where they were taken care of by Dr. Karol Estreicher. From France, the books sailed aboard the ship Chorzów to England, and then aboard the ship Batory to Canada. After a 20-year journey, on 3 February 1959, the volumes returned to Warsaw, and on 24 February the Bible was handed over to its rightful owners. The next day, Fr. Liedtke brought it to Pelplin and placed it in a specially commissioned safe. It remained there as a treasure of the seminary library until the 1980s. In 1982, Fr. Dr. Roman Ciecholewski, then appointed director of the Diocesan Museum, was tasked with consolidating the dispersed collections and fully inventorying them. For almost 10 years, the museum displayed the Bible in its original form, after which the volume was returned to the safe. In 2002–2003, a facsimile was created, and from that time on, only the facsimile was exhibited, while the original could be admired only during important events related to the history of Pelplin or the diocese.

However, voices calling for one of the most valuable written monuments in Poland to be taken out of the treasury were becoming more and more frequent. – By decision of Bishop Ryszard Kasyna, a scientific and conservation commission was convened, and after the initial inspection, we already knew that the Bible was not in the best condition – says Prof. Raczkowski. – We took micro-samples for preliminary tests to diagnose the problem, and it turned out that in some places, the books were in dramatic condition. That's why we launched the project "We Are Saving the Pelplin Gutenberg Bible", because to display it, we first had to save it.

Effects of the Exile

Several dozen scientists and conservators of paper, leather, and metal from Poland and abroad took part in the interdisciplinary, cross-disciplinary research and in the conservation and restoration work. In addition to the large group of researchers from the Faculty of Fine Arts at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, the project also involved staff from the AGH University of Science and Technology in Kraków, the Department of Microbiology at the Kraków University of Economics, the Institute of Microbiology at the University of Warsaw, the specialized research spin-off company RDLS Ltd. from the University of Warsaw, the Laboratory of Instrumental Analysis at the Faculty of Chemistry at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń; PCB Service in Pruszcz Gdański, Keyence Poland in Warsaw, and the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures / Cluster of Excellence / Understanding Written Artefacts at the University of Hamburg.

photo Project archive "We Are Saving the Pelplin Gutenberg Bible"

– For such an old object, the first incunabulum that came off the first printing press, the Bible looked quite good – claims Prof. Raczkowski. – Unfortunately, as I've mentioned, this was a deceptive impression. After thorough analysis and research, we know that the books had never undergone comprehensive conservation treatment, so the medium on which they were printed was in very poor condition: the paper was damp and, in some areas, in an advanced stage of decomposition. If someone were to turn the pages clumsily, grabbing them by the corners, they might end up with them in their hands.

It's no surprise. In 1939, a Pelplin leatherworker made a special case in which the Bible first sailed from France to England, then from England to Canada, and afterward lay for several years in the basement of the Bank of Montreal in Ottawa. After returning to Pelplin, it only once left the town's borders. It was transported to Toruń for a CT scan. The "trip" lasted about five hours, and the scan was carried out at the Municipal Hospital between 5:00 and 6:30 a.m. The volume was escorted by an armed convoy, and only a few people knew the route, date, and time of the journey.

At the end of the 1920s, the Diocese of Chełmno briefly considered selling its Gutenberg Bible to raise funds for the renovation of the cathedral and the expansion of the seminary. Although the idea was quickly abandoned, it is said that offers of around one million dollars continued to arrive until the outbreak of the Second World War. So, it is not surprising that, after invading Poland, the Nazis meticulously searched for the volumes, and after the war, a query came from Canada asking whether the 1929 offer was still valid. Today, it's difficult to even estimate the value of the Pelplin Gutenberg Bible. Online, amounts between 30 and 50 million dollars appear, but it's hard to say how realistic they are. For comparison, in 2022, a rare print of Nicolaus Copernicus's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium was sold for 2.2 million dollars.

Home Laboratory

Aside from the CT scan, all conservation work was designed so that the Bible would not leave Pelplin – to avoid altering its conditions or exposing it to further damage. The team from Hamburg, which studies manuscripts, brought mobile scientific equipment (MoLab) worth millions of euros, and the researchers expanded and outfitted the conservation workshop at the Pelplin Diocesan Library. As a result, it was the research equipment that came to the Bible, not the Bible to the laboratories.

photo Project archive "We Are Saving the Pelplin Gutenberg Bible"

– After examining the Bible, we organized a meeting with the bishop and informed him that we would like to carry out a preventive conservation project with a full research and scientific component, followed by dissemination – explains Prof. Raczkowski. – We did not aim to end up with a “new" Bible – after all, we already have a facsimile – but rather wanted to focus on stabilizing processes, halting the destructive processes occurring within it. We also wanted to preserve all the historical elements – the marks of time – that this book carries. The conservators even left some stains intact, as they are traces of history, so those that posed no harm were retained. Someone unfamiliar with the matter, comparing the volumes before and after conservation, might say they barely differ.

Researchers – and above all, female conservators – from the Department of Paper and Leather Conservation-Restoration at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Nicolaus Copernicus University performed extremely meticulous work, removing moisture from the pages. – We know almost nothing about any previous conservation efforts – says Prof. Raczkowski. – We determined only that the Bible had undergone disinfection. Thanks to innovative research on volatile organic compounds – the so-called “electronic nose" – conducted by Dr. hab. Tomasz Sawoszczuk, Prof. of the Kraków University of Economics, we were able to identify the substance used at the time. It was fairly common during the communist era and had a distinctive smell that could be sensed when opening the Bible. The volume was dried, and the unpleasant odor eliminated. This required painstaking effort, repeatedly interleaving the pages – all 1,300 of them – with special material.

photo Juliusz Raczkowski

The covers were in very poor condition. – The Bible was bound in the bookbinding workshop of Henryk Coster in Lübeck – says Prof. Raczkowski. – Minimal infill work was done to repair missing parts, only where necessary to maintain the structural integrity of the codices – for example, at the spines, where they were vulnerable to mechanical damage. This was done in such a way that anyone could see the repair and nothing pretended to be original.

The scholar emphasizes that the Pelplin Bible is the only copy in the world whose complete history is traceable. For instance, it is known that the Berlin Bible came from the library of the Electors of Brandenburg, but how it got there remains unknown. It may have been purchased – although that's unlikely – or taken from an unknown, now-dissolved monastery. – We know everything about our Bible – assures Prof. Raczkowski. – We know the full composition of Gutenberg's ink; we know what he used lead or copper for in the ink – whether as a drier or a pigment. We can reconstruct the creative process step by step. We know where the tree used for the covers grew and when it was felled. We are certain that the Bible was bound in Lübeck, as the bookbinder “left his mark" on the covers. We know the history of the volumes from their arrival in Royal Prussia practically to the present day. That is their extraordinary value.

photo Juliusz Raczkowski

The first stage of the project – including research, conservation, digitization, and making the Bible available online – and the second stage – comprising integration of research findings, promotion, publication, and dissemination – lasted three years and cost over one million PLN. The first phase was jointly funded by the ORLEN Foundation for Pomerania and the PKO Bank Polski Foundation, with part of the costs covered by the Diocese of Pelplin. The second stage was financed by the ORLEN Foundation for Pomerania, with a 10% contribution from the diocese.

NCU News

NCU News